A new teaching system, revolutionary in more than one sense, has been developed and tested in secret. Known as the 360 degree flexible classroom, it challenges the techniques used by teachers down the ages.

Although the year eight boys of St Margaret’s High School in Aigburth look conventional enough as they file into class in their ties and blazers, they are effectively entering a Tardis full of futuristic gadgetry.

When their afternoon maths lesson begins, far from having to keep themselves awake by flicking elastic bands at each other, they are careering around the room on wheels.

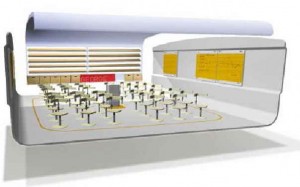

Instead of simply standing at the front, their teacher, Tim Wadsworth, circles them on a curved ‘racetrack’, occasionally taking up a position on a podium in the centre of the room. No longer can reluctant students skulk at the back of the class or plant themselves on the periphery of the teacher’s field of vision.

To the outsider the scene looks chaotic, but for the designers of this prototype and the children who have studied in it, the classroom is a hit.

Twelve-year-old pupil Daniel Pinder, who has maths and German lessons in the new round room, explained the benefits of the pilot project. ‘We do much more group work now – it is better because of the shape of the room. If the teachers ask us to get into groups of four we just take the brakes off our chairs and move,’ he said. His classmates sit at their own Q-Pods, special table and chair units on wheels.

During a typical lesson last week the boys sat in sets of four, hunched over large white boards, discussing work and gripping thick marker pens. As Wadsworth circled his pupils, one boy chucked a board cleaner at a friend, while another drew round the shape of his hand, but most were clearly engrossed in their tasks. It may have been a maths class but it could easily have been an art class, to judge by the level of physical activity.

The white writing boards fit back on to the walls of the classroom so the class’s work can be discussed. To see this, the boys swivel round on their seats, before swivelling back into a semi-circle around the teacher to examine a diagram.

The wall boards can also become screens for computer projections, while the temperature and light in the room are electronically controlled. Mirrors mounted at three points serve as eyes in the back of the teacher’s head.

Thirteen-year-old Anthony Robson is impressed. ‘In a normal classroom they cram everything on one board and you can’t see it. The only bad thing about this classroom is its location – if the teacher is late we have to stand in the rain,’ he said.

The flexible classroom is one of 10 Design Council learning campaign projects set up in schools around Britain. Constructed last year, it has been in regular teaching use all this term. Now the Design Council hopes the project will influence the way every school is built, ahead of a huge national education investment programme.

The government is to spend £5.2 billion on refurbishing and building schools in the first major investment for three decades. On top of this sum, each year over £1bn is spent on furniture, decoration and maintenance.

The Design Council team believe this money should be spent with imagination, rather than just copying the old fashioned classroom blueprints. When schools are given money they think, “Great, we can have a new computer lab,” but they do not really think about the environment,’ said Toby Greany of the Design Council. ‘This classroom works so well because the racetrack around the room means there is no back of the class. There have been some teething problems but this is only a protoptype.’

David Dennison, headmaster of St Margaret’s, said he had been unhappy with traditional classroom design for some time. ‘I felt it didn’t suit modern teaching,’ he said.That doesn’t mean we don’t use modern skills here, but it involves moving a lot of furniture. So we were completely sold on the idea of classroom that would operate in many ways at one time – for role play and for projecting on to a number of surfaces.’

Thirteen-year-old pupil Phillip Harper agreed. ‘It is much better than other classrooms, the chairs are better, you can spin around and see the teacher.

‘It is also much more fun. We get the boards down all the time and work together – before we would work more on our own in maths. This has made maths much more fun than it used to be,’ he said.

The Department for Education and Skills has supported the scheme and watched with curiosity. Mike Gibbons of the department’s innovations unit, which also supported the Joined Up Design For Schools project now on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, has been impressed.

‘What you need is as much flexibility as possible when building schools,’ he said. ‘What you don’t want to do is to trap yourself into one design. The 360 degree classroom is wonderful. It offers maximum flexibility.’

Building a small-scale prototype is widely acknowledged as the best way to create certainty about future teaching and learning needs. Stakeholder Design can help you build capacity, explore the future and prepare for change. All of this reduces risk, meaning that it generally pays for itself.